From the March 9, 2009, Princeton Weekly Bulletin

Most people traveled to the 2008 Beijing Olympics for the sporting events and pageantry. Anna Michel went for the smog.

Michel traveled to China as part of an interdisciplinary team of researchers from Princeton and Rice universities to study changes in Beijing's air quality during the Olympics, when the Chinese government dramatically cut vehicle and factory emissions.

The Olympics provided a rare opportunity for the researchers to test laser-based sensors that may provide a cheaper and more effective way to study how air pollution affects climate and human health in a region.

The project also tested the team's ability to navigate complex international research programs, as the focus of their study -- Beijing's polluted skies -- sparked controversy during the games. The researchers made an agreement with the Chinese government that data from their study would not be released until 2009. "That was a big challenge that we faced, because the data was so sensitive," said Michel, a postdoctoral researcher at the Princeton-based Center for Mid-Infrared Technologies for Health and the Environment (MIRTHE).

To the Chinese government's relief, Beijing's air pollution diminished during the games -- and much of the controversy with it. The Princeton team was left to determine if it was simply a lucky shift in the weather or if the efforts to curb emissions helped produce the clear skies.

The project was sponsored by MIRTHE, a partnership of six institutions that seeks to develop ways to use new quantum cascade laser technology to measure airborne chemicals. The center was established with a $15 million National Science Foundation grant in 2006 and is led by Claire Gmachl, a Princeton electrical engineering professor.

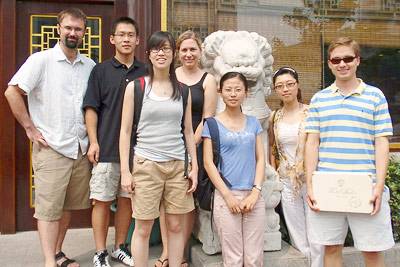

Students and postdoctoral researchers from Princeton and Rice universities participated in the Beijing air-quality study. The research was sponsored by the Princeton-based Center for Mid-Infrared Technologies for Health and the Environment (MIRTHE), which seeks to develop ways to use new laser technology to measure airborne chemicals. (Photo: Anna Michel)

Ten members of the MIRTHE team, which included Princeton engineers and climate scientists and researchers from Rice, arrived in Beijing prior to the start of the Olympics. They were guests of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The team mounted two laser-based sensors at China's Institute of Atmospheric Physics, a building located just a couple of miles from the Bird's Nest, the giant stadium that served as the venue for the opening and closing ceremonies of the Summer Games.

One of the devices was a quantum cascade laser open path sensor, which emits a beam of light that can travel up to a kilometer to a reflector that bounces the beam back to its original source. The other sensor collected air samples at a single point and then passed a beam through the air in an internal chamber.

The sensors work on the principle that different gases in the air absorb different wavelengths of light, so the gases leave their signature on laser beams that pass through them. By analyzing those signatures, the researchers measured the concentrations of certain gases in the Beijing air.

To monitor Beijing's air during the Olympics, the researchers used sensors like the one pictured here that measure airborne chemicals using quantum cascade lasers. (Photo: Anna Michel)

The sensors made continuous recordings from mid-July to the end of August, focusing on measuring levels of trace gases, such as water vapor, ammonia, carbon dioxide, nitric oxide and ozone, which can affect climate and human health in a region.

The goals of the project were twofold, said James Smith, a Princeton professor of civil and environmental engineering who co-led the project along with Gmachl and Gerard Wysocki, another electrical engineering faculty member.

The researchers wanted to study the specific effect that curbing pollution had on Beijing's air quality. At the same time, they wanted to test whether their laser-based sensors could provide an affordable means to study climate and air quality in other regions of the world.

In the United States, Smith said, the government currently uses networks of sensors to monitor air quality for compliance with state and federal regulations. The high cost of environmental sensors limits their utility for scientific study.

The laser-based sensors developed by the MIRTHE team provide continuous, real-time readings of air quality. Smith said they might one day provide a cheaper alternative to current air-quality sensors that often require bulky, expensive machines to analyze samples.

To study global warming and other atmospheric phenomena, climate scientists have used satellite imagery to gather data and develop mathematical climate models. But the bird's-eye view provided by satellites is not sufficient for the study of climate at a finer scale.

"In many cases, the problems we are dealing with are regional in nature -- for instance, determining whether drought in the U.S. Southwest is just bad luck or a new climate regime," he said. "In the case of Beijing, the city had suffered from decades of decreasing rainfall, so determining whether Beijing's pollution problem is contributing to the lack of rain is a big deal."

Smog obscured the view of Beijing's Bird's Nest stadium prior to the start of the Olympics, but gave way to clear skies during the games. (Photos: Gerard Wysocki)

The Olympics offered a chance to test the laser-based sensors in a real-world setting, to see if the devices might be deployed in networks that, among other things, would help scientists assess the accuracy of the computer models used for climate research.

"It was an uncommon opportunity to see a system perturbed," Smith said, referring to China's attempts to limit pollutant emissions just before and during the Olympics. "We had very good information on what the emissions were and how they changed over time."

It also was a chance for the researchers to practice their skills at diplomacy. Prior to the Olympics, Beijing's polluted air became a topic of controversy in the media, and the Chinese government went to extraordinary lengths to clean up the air for the games. Cars were banned from roads, and factories near Beijing were ordered to shut down during the games.

Smith said the delicacy of the situation and the negotiations with Chinese government officials provided a teachable moment. "It helped the junior members of the team develop an understanding of how complex scientific programs play out in an international setting," he said.

Aishwarya Sridhar, a senior in electrical engineering who spent a month in Beijing working on the project, said the experience taught her how to collaborate with people from other disciplines. "You had to interact with people from a lot of different backgrounds, who may or may not speak the same language," she said.

It also broadened her perspective on the kind of work in which electrical engineers are involved. "You can be the electrical engineer in a group that does things that you wouldn't think of as electrical engineering -- like climate science," she said.

When she first arrived in Beijing, the skies were dingy and visibility was poor, but the air cleared during the Olympics. The researchers are now trying to determine if it was just good luck or if curbing emissions played some role. They hope to publish the first of the results sometime next summer.

Smith said that emissions of pollutants from car exhaust dropped significantly over the course of the experiment. "The big question," he said, "is whether this was a factor in the clearing of the skies during the Olympics."

MIRTHE plans to continue its global research this spring by sending the open path sensor to Ghana to measure air quality in a region where burning of plant matter for energy and food processing pollutes the skies.