Rachel Price, an associate professor of Spanish and Portuguese who is also affiliated with the Program in Media and Modernity, joined Princeton in 2009. Her scholarship focuses on Latin American, Caribbean and particularly Cuban literature and culture; media; poetics; empire; and ecocriticism. Her essays have explored a range of topics including digital media, slavery, poetics and visual art. This semester she is teaching an undergraduate course, "El Género Negro: Crime Fiction," in Spanish, and a graduate course, "Narrative Prose in Latin America — Finance and Form."

In her new book, "Planet/Cuba" (2015, Verso Books), Price addresses contemporary literature as well as conceptual, digital and visual art from Cuba that engages questions of environmental crisis, new media and new forms of labor and leisure.

Why did you decide to write a book about contemporary Cuban artists focused on the decade since Raúl Castro assumed power in 2006?

Price's new book "Planet/Cuba" addresses contemporary literature as well as conceptual, digital and visual art from Cuba. (Photo courtesy of Verso)

I first went to Cuba in 1998; from 1998 to 2000 I was the coordinator of the Social Science Research Council/American Council of Learned Societies' Working Group on Cuba, a program that aimed to improve relations between U.S. and Cuban academics. Over the next 15 years I returned to Cuba scores of times for work and for my own research.

My first book, "The Object of the Atlantic: Concrete Aesthetics in Cuba, Brazil and Spain 1868-1968" (2014, Northwestern University Press) had two chapters on Cuban literature and culture from the 19th century through the 1940s. But as I was researching these and other topics, I was also observing the many post-Soviet changes Cuba was undergoing. In the late 1990s the characteristics and culture of the “"Special Period" — the government's term for the hardest years of punishing scarcity following the end of the Soviet Union—were still very palpable. By 2010, though, things were quite different. So while I was carrying out research on the past, I remained very aware of what was happening all around me, and of the significance of economic and other reforms inaugurated by Raúl Castro, who took over informally in 2006 and formally in 2008.

My first book ended with a study of 1960s experimental poetry and art in Brazil, and in particular with some of the earliest Latin American computer art. It seemed natural to bring together my interests in new media with my longstanding research in Cuba.

What did your research process look like?

Around 2008-09 I began researching digital art and literature in Cuba and in 2011 published an article on bloggers, digital aesthetics and new media art in a special issue of the journal Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas on Cuba. That same year, I also presented research on 1960s computer art at a conference at Cuba's Superior Art Institute's department of audiovisual communication arts. There I met the curator and video game artist Rewell Altunaga, who gave me a catalog of an exhibition of some 100 young Cuban artists working in a variety of media, from painting to performance, land art, digital media, etc. I became very interested in the work, and while there I met with several of the artists in their studios. Around the same time, I spoke with the digital poet Samuel Riera (who is also an artist and gallerist) and was struck that he framed his own evolving interests specifically in terms of the changes Cuba was undergoing. He noted that the move from Fidel Castro's internationalist ambition and rhetoric to Raúl Castro's more mundane, pragmatic vision meant that he (and other artists) felt freer to train their sights on more local problems. For example, through his art, he began exploring ecological questions related to the closure of the sugar industry and energy independence. So it was really through observing, researching and talking with artists and writers that I grew interested in writing about what was emerging and what new art and writing was being made.

About that slash in the title "Planet/Cuba." How does the title illuminate your exploration of Cuba as both insular and global — or, as you describe, "a crossroads of the Americas and Europe?"

I wanted to indicate that many of the questions I look at in the book are both a product of Cuba's singular history and are common to other places too; that they are increasingly global questions, and not examples of Cuban exceptionalism. Deindustrialization, the diminishment of a welfare state, informal economies, environmental crises, authoritarianism, but also innovation, creativity, resourcefulness — we see these not just in Cuba but around the globe.

I also wanted to think about the many positions Cuba has occupied in its own imagination and for the rest of the world. Cuban history has always been inescapably global, shaped by empires, by massive slave trade, by the island's sitting at the junction of international trade routes. Its history has also impacted that of many other countries. Both because of and despite this, Cuba is often discussed as singular: sometimes as a theme park, or as a world apart, as a kind of "Planet Cuba."

By introducing the slash, I also wanted to call attention to the indissociable relation between Cuba and the planet. The Cuban cultural critic Ambrosio Fornet once wrote that he and his friend and novelist Jesús Díaz, eventually a sharp critic of the Cuban revolution, were "fused at the spine of that igneous couple — Literature/Revolution." I wanted to get at something like that kind of relation, one that is necessary even as it is in tension. I wanted to stress the planetary dimensions of the island's challenges and promises today: planetary in the sense of not particular to its history, and planetary in the sense of having to do with the planet.

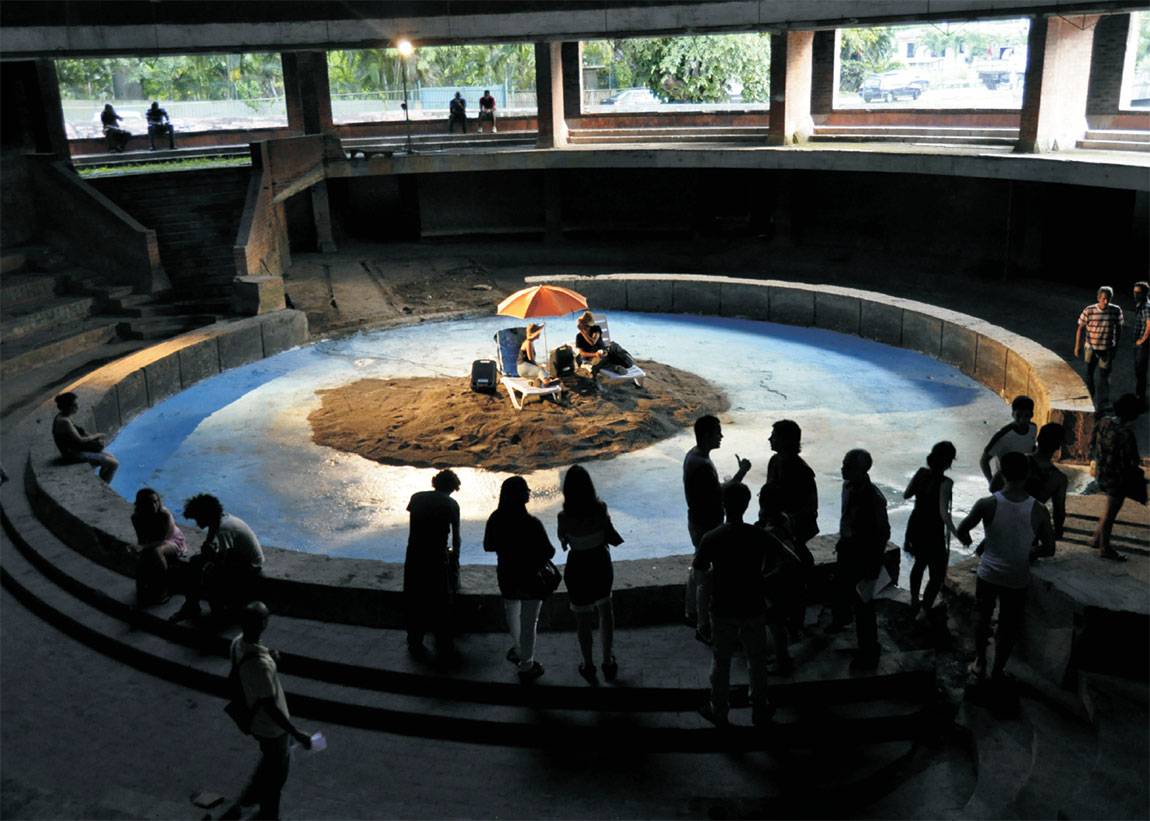

In "Absolutamente tropical [Absolutely Tropical]," a 2014 site-specific work, artist Rafael Villares, Price says, set out to construct an experimental space in the ruins of one of the unfinished buildings of Havana's Instituto de arte superior [Higher Art Institute] to test how contemporary art world behavior mirrors behavior in daily life. (Photo courtesy of Rafael Villares)

How did you identify the different art forms you wanted to discuss, including visual arts, science fiction, literature and film?

It was a quite organic process: During my many research trips, I was talking to writers, making studio visits, letting one suggestion or interview lead me to another, reading and looking at a wide range of materials. I lived there in September and October of 2013 as I was writing and researching.

In "Afluente [Effluent]," a 2009 installation, artist Humberto Díaz sunk a 1974 Ford Maverick in concrete — he had hoped for a Mustang, explains Price, but its owner didn't want to see it destroyed. Díaz noted that he was interested in working with fetish objects; with the importance of the automobile for contemporary life. (Photo courtesy of Humberto Díaz)

The book has a strong emphasis on ecology. How are artists addressing issues of climate change and issues such as the impact of deforestation in Cuba?

I talked to one Cuban author who said that ecological concerns come from the North American academy — but then admitted that his own novels foreground such reflections! People seem to think of environmentalism as something like "Save the Whales" campaigns, but in fact so much of life in Cuba, like anywhere on the planet, is deeply marked by an engagement with the environment: in cities, where food security is an issue; in the countryside, where drought is an increasing problem and where invasive species at once restore nitrates to land worn out by sugar but also thwart agriculture; in the waters, where fishing is diminished. At the same time, Cuba has what many experts believe to be the healthiest environment in the Caribbean, thanks to both passive and active conservation efforts (passive because of a lack of development and diminished petrochemicals after 1990; active because of strong environmental legislation).

The government makes much of its environmentalism but skepticism about such self-serving discourse doesn't meant there aren't also many people, from agronomists to biologists to artists, deeply committed to working on challenges facing the environment.

As for deforestation on the island, it is actually less of a problem today than during its nadir in the 1930s, when the sugar industry was expanding.

Artists and writers engage ecological questions both on the local and global scales: they may, to give just a few examples, make humorous video art about the failures of agricultural reform in Cuba, create installations ("environments") that involve living trees, or write speculative fiction — another term for science fiction — that imagines mass migrations caused by ever-increasing hurricanes in the Caribbean.

How does art-making in Cuba reflect issues of surveillance and state security?

Cuban art varies widely in media and content, spanning everything from photography and painting (figurative, abstract, 3-D printing) to performance, sound art, conceptual and post-conceptual art, etc. So to address any one theme or approach as dominant would be misleading. Artists who do engage the themes and technologies related to surveillance and state security do so through a variety of approaches: by hacking into systems of transmission and rebroadcasting information; by creating exhibits that force viewers unwittingly to participate in being surveilled; by producing video game art that simulates a famous panopticon prison; by creating spaces of free speech amidst strict monitoring; and so on.

What interested me in particular was the way that such art today thematizes the particularities of Cuba's network of vigilance, but goes beyond it to comment on or intervene into the more pervasive global systems of surveillance (both state and corporate) in which we all participate.

How are artists interpreting or reacting to the influx of tourism and the country's transition to a market economy?

Many artists have long participated in a global art market, both in terms of selling works and in terms of international residencies, and so on. That said, there is definitely still greater circulation over the past few years as restrictions on travel have been removed, more curators and museums have been visiting, and new galleries have opened.