This fall, six Princeton undergraduate students in the course “Arts of the Medieval Book” are exploring the technology and function of books through a historical perspective.

Working firsthand with Princeton's collections of centuries-old illuminated manuscripts and facsimile editions of some of the most visually splendid manuscripts made between the sixth and 16th centuries, the students consider the choices artists made as they married text and image. At the end of the course, the class engages with contemporary artists' books to explore how book forms have evolved.

Students in the fall course “Arts of the Medieval Book” are exploring the technology and function of books using a historical perspective — working firsthand with Princeton's collections of centuries-old illuminated manuscripts and facsimile editions. Pictured here: The class views original manuscripts in Princeton University Library’s Division of Rare Books and Special Collections with Beatrice Kitzinger (center), assistant professor of art and archaeology, and Don Skemer, curator of manuscripts (third from right).

The instructor: Beatrice Kitzinger, assistant professor of art and archaeology, specializes in Western medieval art. She primarily studies manuscripts from the late eighth to early 10th centuries made in the Carolingian world.

The physicality of manuscripts figures deeply in her teaching. By designing the course around objects in Princeton's collections and asking the students to try some hands-on design work themselves, Kitzinger said students can focus on the "architecture" of bookmaking. This offers a more tangible learning experience than viewing slides. Students have the option to create an original artist’s book for their final project.

At Princeton University Library’s Division of Rare Books and Special Collections, the students viewed “Le roman de la rose (Romance of the Rose),” written in Old French and copied and illuminated in Paris, mid-14th century. “The Rose” — a bestseller of the 14th century — tells the story of a man who falls asleep and dreams of a love that at first he can't have but reaches in the end. The illuminations on page one depict the man sleeping and the beginning of the dream. Garrett MS. 126: Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun.

The materials: Students examine a range of sacred and secular works including Bibles (Hebrew and Latin), psalters and Books of Hours, Haggadot, medical and health manuals, genealogies, apocalypse manuscripts, books on natural science, courtly life, and more.

Visiting the collections: Classes meet in the Marquand Library of Art and Archaeology, where students see high-end facsimiles of medieval works, or in the Division of Rare Books and Special Collections of the Princeton University Library and Princeton University Art Museum, where they can study original manuscripts. The class this semester also included a trip to the Morgan Library in New York.

On a recent Monday, students gathered at one end of a table in a climate-controlled room in the suite that houses Rare Books and Special Collections. They viewed two original manuscripts from the Robert Garrett Collection that were donated to the Princeton Library in 1942 by Garrett, an 1897 alumnus and former Princeton trustee.

Don Skemer, curator of manuscripts, placed a mid-14th-century manuscript, "Le roman de la rose (Romance of the Rose)" on a foam "cradle." He said about 300 complete "Rose" manuscripts survive, and Princeton holds two. The one the class saw was written in Old French and illuminated in Paris.

Kitzinger explained that the "Rose" — about a man who falls asleep and dreams of a love that at first he can't have but reaches in the end — was one of the most widely read and admired medieval French works of literature.

Indicating the four images on the opening page, she asked: "Start to pay attention to some of the choices the painter is making. If we had a 'Rose' manuscript with no pictures, where would the images be?"

"In your head," one student said.

"Yes," Kitzinger said. "You've got whatever's happening in the text in your mind, and these images provide another level for engagement, a counterpoint or comparison."

As Kitzinger turns the pages of "Romance of the Rose," the class discusses the choices the artist made regarding what aspects of the story to illustrate and the marriage of text and images, as well as the book’s “architecture.”

Kitzinger carefully turned the pages; after choosing another section to focus on — where the man enters a garden — she removed the protective tissue paper in between the pages, then laid a velvet weight across the top corners. She asked, "Who's up on their mythology?"

Sophomore Lydia Gompper looks at “Romance of the Rose.”

One student identified the figure of Narcissus. "Narcissus is a prime example of failed love in this poem: he looks in the mirror and falls in love with himself," Kitzinger said. She encouraged the students to think about how the author's choice to depict Narcissus offers "a mode of experience ... opening up a way in which you can think about the process of reading as a process of seeing."

The second manuscript, a psalter (book of psalms for liturgical or devotional use), was copied and illuminated in England at the end of the 13th or beginning of the 14th century, Skemer said.

Holding one page vertically between two fingers, Kitzinger said: "If you move it around a little, the page catches the light differently. See what's going on with the gold in the background. There are designs worked into the gold with a hard point, dots and scrolling vines."

As the students leaned in to look closer, Kitzinger pointed to a faded area and asked, "Look there, what have you got?"

One student said she could see "a sense of the under-drawing, how the figures were prepared and how the color was put on top."

A bevy of experts: Kitzinger said the course would not be possible without the "fantastic generosity" of the curators and librarians. Their opening of the collections and sharing their own expertise allow the students "a combination of serious grounding in the historical objects and a flexibility in the way they interpret what they see, because they can experience so much material."

Don Skemer: "Students have grown up with computers, smartphones and the digital universe. They are eager to learn about older information technologies, from ancient papyri and medieval manuscripts, to hand-printed books, early photography and even typewriters. Viewing manuscripts close up, especially when they are 700 years old, gives students a feeling of closeness to the distant past and provides a sense of physical scale that cannot be easily replicated in digital images."

In the Division of Rare Books and Special Collections, the students also viewed a psalter (book of psalms), copied and illuminated in England at the end of the 13th or beginning of the 14th century. The image on this page, from the prefatory cycle, depicts Pentecost with the Virgin Mary, Apostles and descending Holy Spirit in the form of a dove. Garrett MS. 35: Psalter.

Holly Hatheway, head of Marquand Library of Art and Archaeology: "Facsimiles are of great interest, especially in teaching, due to the limited access to original manuscripts. We also connect professors and researchers to related items that enhance the [academic] experience."

Julie Mellby, graphic arts librarian, Rare Books and Special Collections, who will show the students examples of contemporary books in December: "While the medieval examples the class will study show how the genre was established, these 20th- and 21st-century examples show how contemporary bookmakers and visual artists broke that model to bring text and image to a reader in unique and surprising ways."

Calvin Brown, associate curator of prints and drawings, Princeton University Art Museum: "Professor Kitzinger is a scholar who delights in working and teaching directly from primary objects. The art museum ... has some fine, rare and unusual works in the Department of Prints and Drawings. Professor Kitzinger has sought out some of these hidden treasures."

Students say: "I chose this class because I’ve always had a deep passion for material culture as a window to the past," said Charlotte Root, a first-year student. "As a child, I used to collect quill pens and inkpots from various museum stores because they simply fascinated me."

She spent hours on one assignment, creating an illuminated page on her own. "This task made me realize how incredibly talented these illuminators were," Root said. "They had to do what I was attempting to do in dim candlelight. They created such beautiful artwork with details so minute it baffles me."

This is the third art history course senior Nancy Wenger, a molecular biology major, has taken. "These courses have provided me with an artistically analytical outlet aside from my scientific major studies," she said.

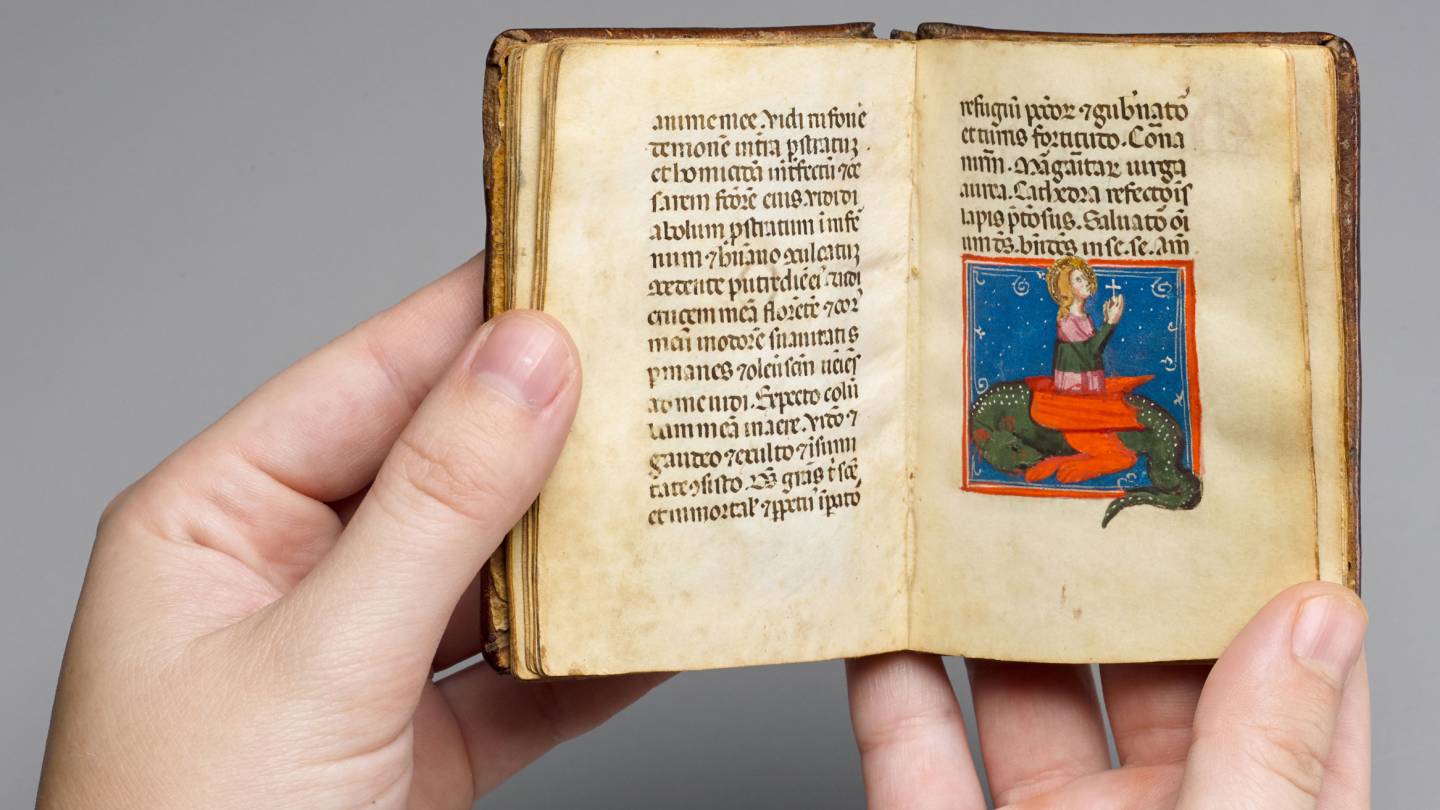

Students also view select items from Princeton University Art Museum’s collections, including this 14th-century North Italian manuscript illustrating the “Life of Saint Margaret.” Measuring only 3 1/4 by 2 3/8 inches, this manuscript was possibly carried as an amulet, and recounts the legend of the popular medieval patron-saint of childbirth. Princeton University Art Museum, gift of Frank Jewett Mather Jr., y1952-57.

Sophomore Isabelle Kuziel said: "I am very thankful and humbled to be at a university with so many incredible resources. I have loved learning about the thought processes that are behind the art we look at because it helps me appreciate the books more."

Sophomore Michaela Hennebury, an electrical engineering concentrator, enjoys the viewpoints of her classmates with different majors. "It has been interesting and valuable to hear the range of observations and opinions that come up in class discussion."

The take-away: Kitzinger compares the experimental work of medieval bookmakers with the ways in which people today are navigating digital media. "I hope that students leave the class primed to look differently at media they might otherwise take for granted, and to be more conscious of how books and other media shape their experiences of reading and thinking."

She said this course, in fact any art history course, is valuable for all students. "Honing the practice of visual analysis and understanding the dynamics in how people organize and present ideas visually are skills pertinent to any major you could name."

To explore how book forms have evolved, the class also engages with contemporary artists' books in Princeton Library’s Graphic Arts Collection and Princeton University Art Museum’s collections, including “Utopian Cannibal” a contemporary printed book by Enrique Chagoya, an artist born in Mexico in 1953. A technically complex, witty work constructed to resemble an ancient Maya codex, the book provides a satirical critique on the history of the political and social relationships between the United States and Latin America by fusing comic, pop-cultural elements with Aztec and Maya religious imagery. Detail of a print from “Utopian Cannibal,” 2000, color lithograph and woodcut with chine collé and collage, 7 1/2 x 92 inches, edition of 30. © Enrique Chagoya. Courtesy of George Adams Gallery, New York. Princeton University Art Museum, museum purchase, David L. Meginnity, Class of 1958, Fund, 2006-50.