Journalist and author Naomi Klein, right, discusses themes related to her bestselling 2014 book, “This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate,” with writer and environmental activist Ashley Dawson. The event was the third installment of the Art + Environment Event Series organized in conjunction with the Princeton University Art Museum exhibition “Nature’s Nation: American Art and the Environment.”

Already the world is experiencing the symptoms of a looming, global environmental crisis, said journalist and author Naomi Klein on Dec. 11 at a talk held in conjunction with the Princeton University Art Museum’s exhibition “Nature’s Nation: American Art and the Environment.”

From warming temperatures to the destruction of the Amazon forests to the treatment of migrants and the poor, the signs all portend a need for climate action on a scale beyond a reduction of carbon emissions, she said.

“We need a shared responsibility for the climate crisis — that countries that have been emitting at industrial scales for hundreds of years need to help those countries that have been at the front lines of climate change, to leapfrog to the next economy, to leapfrog over fossil fuels,” she said.

Before a crowd in McCosh Hall, Room 50, Klein, the Gloria Steinem Endowed Chair in Media, Culture and Feminist Studies at Rutgers University-New Brunswick, discussed her bestselling 2014 book, “This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate,” with writer and environmental activist Ashley Dawson, a professor of English at the City University of New York’s Graduate Center. Dawson was the 2017 Currie C. and Thomas A. Barron Visiting Professor in the Environment and the Humanities at the Princeton Environmental Institute (PEI).

The discussion, which was hosted by the Princeton Environmental Institute and the Princeton University Art Museum, was held Dec. 11 in McCosh Hall, Room 50.

The event, originally scheduled for November but postponed due to a snowstorm, was the final installment of the Art + Environment Event Series organized in conjunction with “Nature’s Nation.”

The series included a talk by author and environmentalist Bill McKibben, the Schumann Distinguished Scholar in Environmental Studies at Middlebury College, as well as a Princeton faculty panel, “Environmental Perspectives on Nature’s Nation.”

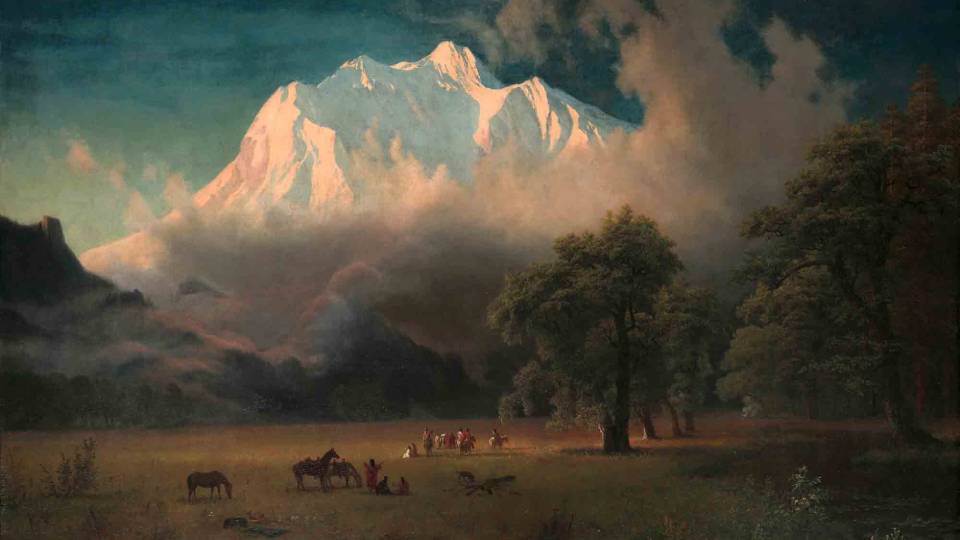

“Nature’s Nation,” which is open to the public through Jan. 6, gathers more than 100 works of art — from the colonial period to the present — to examine how American artists have both reflected and shaped environmental understanding, while contributing to the emergence of a modern ecological consciousness.

In introducing Klein and Dawson, Karl Kusserow, the John Wilmerding Curator of American Art, co-curator of “Nature’s Nation” and a lecturer in art and archaeology, thanked PEI, which co-organized all three events, for being “wonderful, steadfast partners through the whole exhibition.”

Dawson, the author of “Extreme Cities: The Peril and Promise of Urban Life in the Age of Climate Change” and “Extinction: A Radical History,” interviewed Klein about her recent book primarily in the context of current global politics. He opened with a question about the rise of far-right political parties in many nations, but especially in Brazil, where newly elected President Jair Bolsonaro has pledged to roll back protections of the Amazon rainforest and Indigenous lands.

In the face of human destruction of the environment, Klein said there have been movements throughout history to reject and resist these impulses.

“I believe as frightening as what is happening on the right is, what is happening on the other side of the political sector is just as important and often doesn’t get as much attention,” she said. “When I wrote ‘This Changes Everything,’ we were in a different political space. … We didn’t have this generation of political leaders like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez,” she said alluding to the incoming congresswoman. “There are many people in the incoming congressional class who are willing to put very bold transformative ideas on the table that would have been unthinkable a decade ago.”

During a question-and-answer session, audience members asked about the political responses to climate change, capitalism and climate justice, and what types of economies and forms of government might support future life on Earth.

Klein said she believes far-right movements are being fueled by “a hyper-nostalgia for the simpler time when men were men and women were women and people knew their places.”

“It’s this toxic cocktail, much of which is familiar in this country, and also the centrality of defending the fossil fuel sector and extractivism,” she said.

The political left, in many places throughout the world, also bears responsibility for the current environmental situation — particularly in extractive economies in South America, where commodities prices were boosted by Chinese growth and demand in recent years.

“Commodities prices were very, very high, and it seemed for a time to make sense just to dig up as much oil and gas in Bolivia, oil in Ecuador, and redistribute the profit,” she said.

Moving forward, the solutions likely will be painful. The protests by the “yellow vests” in Paris over increased gas taxes intended to protect the environment are one example of the need to incorporate social and economic justice with climate policy, she said.

She recounted a quote by one of the protestors who said, “Those rich people care about the end of the world, but we have to care about the end of the month.”

Of the “Green New Deal” being proposed by environmentalists and political leaders as a way to address both climate change and a potential economic downturn, Klein said, “It’s recession-proof in a way that climate policies have not been in the past.” But she said it must prioritize the most-oppressed communities.

“Why not retrofit some of those GM factories that are being closed,” she said, suggesting a focus on building electric buses and light rail.

In looking for growth in “low-carbon work,” she also said the “Green New Deal” could emphasize the arts.

“One of the most important roles artists can play is to help us imagine a future that isn’t like this,” Klein said.