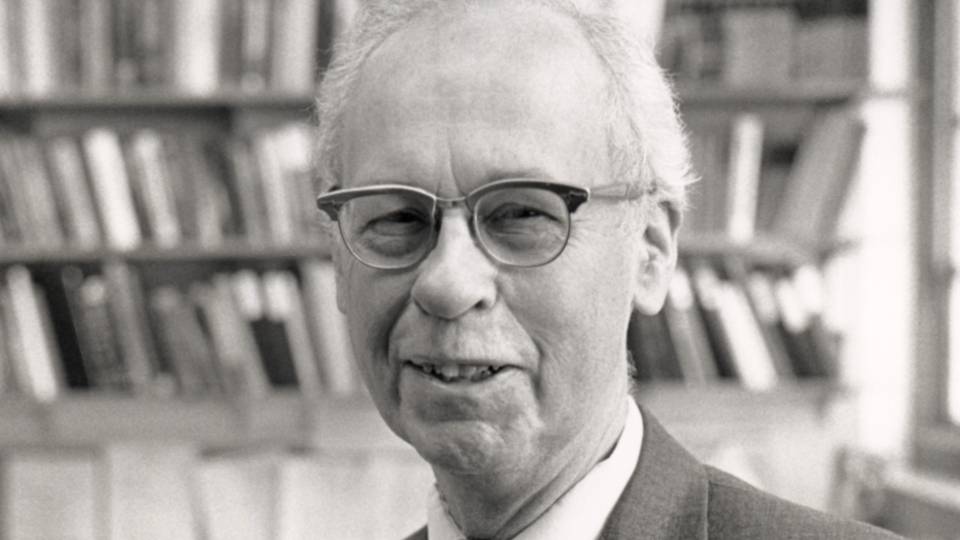

Edward Stiefel, a gifted Princeton chemist who bridged the fields of

industry and academia, died Sept. 4 in New Brunswick, N.J., from

pancreatic cancer. He was 64.

Stiefel, the Ralph W. Dornte Lecturer with the rank of professor,

joined the chemistry faculty in 2001 after retiring from ExxonMobil.

"Ed was a wonderful colleague, a generous and compassionate friend, and

an inspiring mentor," said John Groves, the Hugh Stott Taylor Chair of

Chemistry at Princeton, who first met Stiefel when they were graduate

students at Columbia University.

A graduate of New York University, Stiefel earned his Ph.D. from

Columbia in 1967. He taught for seven years at the State University of

New York-Stony Brook, then served as an investigator and senior

investigator at the Charles F. Kettering Research Laboratory.

In 1980, he joined Exxon as a research associate. Over the next 21

years, he became a senior research associate, scientific adviser and

senior scientific adviser. He was a scientific architect of the cleanup

of the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska in 1989, applying the

principles of bioinorganic chemistry and microbiology to this

large-scale environmental remediation project. He also was the inventor

of the commercially important "thiomolybdate" additive for lubricating

oils.

Stiefel held 30 U.S. patents and published more than 150 scientific

articles. His review article on "The Coordination and Bioinorganic

Chemistry of Molybdenum" has been cited in more than 800 publications.

He was co-editor with Harry Gray, Joan Valentine and Ivano Bertini of

the recently published book "Biological Inorganic Chemistry."

Stiefel was a member of the board of reviewing editors of Science

magazine, a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of

Science and a winner of the American Chemical Society Award in

Inorganic Chemistry in 2000. He was founding co-chair of the Molybdenum

and Tungsten Enzymes Gordon Conference (with Russ Hille) in 1999 and of

the Inaugural Gordon Research Conference on Environmental Bioinorganic

Chemistry (with François Morel) in 2002.

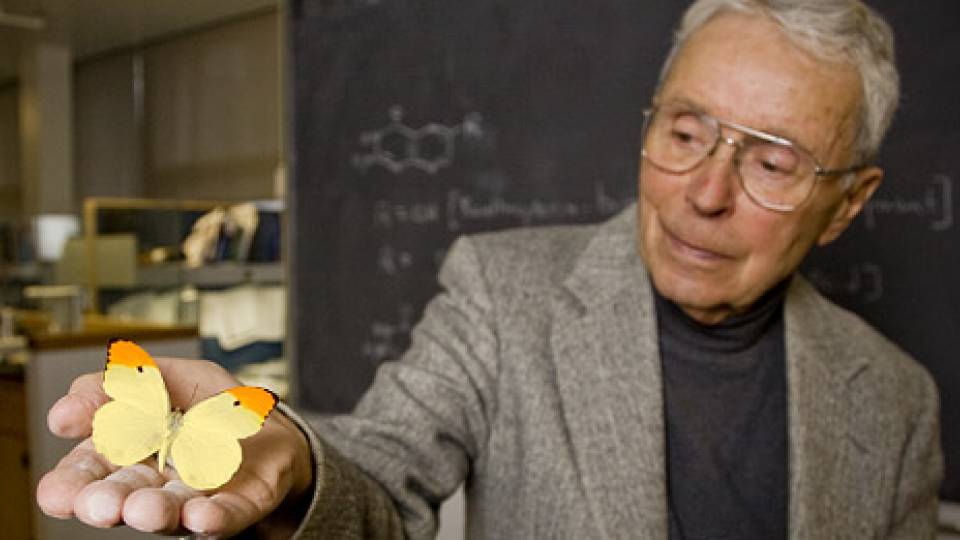

At Princeton, Stiefel was affiliated with the Princeton Environmental

Institute in addition to the chemistry department. His research

interests included the bioinorganic, coordination and environmental

chemistry of transition metal ions. He was a key principal investigator

(with Charles Dismukes) in Princeton's bio-solar hydrogen program.

Also a talented teacher, Stiefel worked with Groves to develop a new

class called "Metals in Biology" that became one of the most popular

graduate courses in the department. In addition, Stiefel taught a

freshman seminar on "Elements of Life." "Ed's genius lay in his uncanny

ability to 'see' complex chemical issues over a wide range of scale,

from global to the molecular," Groves said.

Another colleague, Michael Hecht, remembers the many wide-ranging

conversations in the hallway with Stiefel, who had the office next

door. "He had the sort of enthusiasm and exuberance that made you

almost feel like he was going to leave the ground," said Hecht, a

professor of chemistry.

"One of us would think about something that was a little bit off-topic,

but related," he said. "Those digressions were sort of parentheses

within a topic, but then we'd come on something else -- there would be

parentheses within parentheses. But you never closed the parenthesis

because you were always planning to get back. When I walk by his door,

I feel like there are dangling conversations still left in the air and

many parentheses that are open but never closed. That was the kind of

person he was. There were always many things going on, one inside of

the other. He was full of knowledge and thought and interest and

concern about a million different topics."

Survivors include his wife, Jeannette, of Bridgewater; and daughter

Karen Hoerhold, her husband, Udo, and their two sons, of New Hampshire.

Funeral services were held on Sept. 6.