Leonard Barkan is the Class of 1943 University Professor of Comparative Literature at Princeton University, where he also teaches in the art and archaeology, English, and classics departments. His scholarship focuses on early modern literature and art history, and theory and practice in the interdisciplinary study of culture.

Barkan completed his newest book, "Berlin for Jews: A Twenty-First-Century Companion" (University of Chicago Press, 2016), on sabbatical during 2014-15, while teaching at Humboldt University in Berlin, and at Harvard University's I Tatti Center for Italian Renaissance Studies in Florence. Part history and part travel companion, "Berlin for Jews" shows how the city's long Jewish heritage, despite the atrocities of the Nazi era, has left an inspiring imprint on the vibrant metropolis of today. View the book trailer here.

Barkan's other recent books are "Mute Poetry, Speaking Pictures" (Princeton University Press, 2012), an essay about the intersecting worlds of artists and writers from Plato and Praxiteles to Shakespeare and Rembrandt, and "Michelangelo: A Life on Paper" (Princeton University Press, 2010).

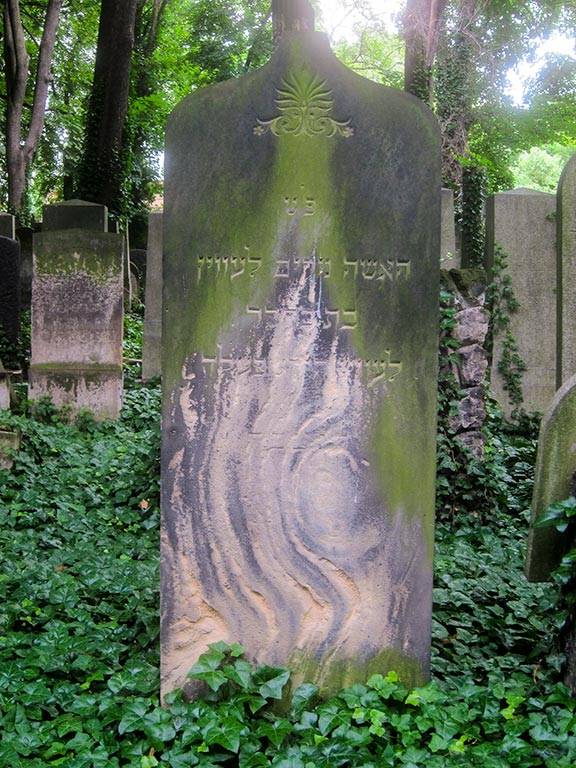

On the gravestones in the Jewish cemetery in Schönhauser Allee, the lettering in Hebrew and the signs of age are visible. (Photo by Nick Barberio, Office of Communications)

How did you come to "fall in love at first sight" with Berlin, and why did you decide to write a book about it?

Falling in love with Berlin was easy. Even casual visitors are often struck by its mix of cultural vibrancy, modern amenities, gorgeous green spaces and lakesides, not to mention the mark of history that it bears. As for the experience that led in particular to this book, on one of my first visits to Berlin, I visited a Jewish cemetery in Schönhauser Allee. What I expected was a desecrated ruin; what I found was a well-ordered landscape of elegiac beauty. I felt that I had entered upon the gracious memorial garden of a particular past in which proud, well-to-do and accomplished Jews had staked their claim on the civilization of a great city. This was a story that most accounts of Jews in Berlin do not tell.

What did your research process entail?

Reading a lot of German, which, luckily I had learned rather well, in part owing to a childhood spent decoding my parents' private conversations in Yiddish. More recently, I found 19th-century accounts of salons presided over by grand Jewish ladies. I delved into the lives of relatively ordinary Jewish citizens whose graves are in Schönhauser Allee. I discovered address books that located a whole range of Jewish Berliners — everyone from Pitsch the plumber to Einstein the Nobel Prize winner. When I came upon particularly handsome buildings in what had been an upper middle class Jewish neighborhood, I found ways to track down the individuals who had lived there; I could tell you who occupied, say, the apartment on the right-hand side of the second floor. It may seem like a meaningless detail, and yet I felt I was returning a society of Berliners to their homes.

This 19th-century row of residential buildings in Kreuzberg escaped destruction during World War II. (Photo by Nick Barberio, Office of Communications)

The book is structured with five chapters. The first two focus on specific areas of the city: Schönhauser Allee and Bayerisches Viertel. Why did you choose these?

Berlin has almost from its origins been divided between East and West (not just after 1945), so I wanted to cover the field and explore both the 19th and 20th centuries. And also different kinds of neighborhoods. In the East, I chose the Schönhauser Allee cemetery, which went into operation in 1827. In the West, I chose the Bavarian Quarter, a residential neighborhood invented in 1900 by a Jewish developer and with a sufficient ethnic identity to be known as the "Jewish Switzerland." Of course, that pair of choices also meant I was choosing one place where people lived and another where they were laid to rest.

These are followed by chapters on three people: Rahel Varnhagen, James Simon and Walter Benjamin. Why did you choose these individuals?

I wanted chronological coverage — and fascinating people. I chose these three because their lives captivated me; what emerged, though, was that each had a complex relation to their Jewish identity and a passionate relation to their home city.

Varnhagen, a Jewess of no great fortune and (as people were all too ready to point out) no great beauty, flourished as the doyenne of Berlin society from the end of the 1700s into the 1830s. She knew everyone from Goethe to Beethoven, and dozens of luminaries were in the habit of sipping tea in her modest attic apartment.

Simon, born in the mid-19th century, was prominent in the life of the city from his young adulthood until his death in 1932. He was a cotton magnate whose philanthropy extended among Jews and Gentiles, but his great passion was art — from works of the Renaissance in his own personal gallery or the vast field of archaeology in Egypt and the Near East, which he bankrolled. Masterpieces like the Nefertiti Head and the Ishtar Gate came to the Berlin museums through his generosity.

Benjamin, born in 1892, represented the cultural Berlin of the early 20th century, including its horrific demise. He was a literary critic and (as I like to call him) the messiah of modernity, who theorized a cultural future that he did not live to see.

The book reveals how Jews became prominent in the arts, the sciences and the city's public life. What do you consider one of the city's hidden gems where readers might learn an unexpected history lesson?

Early in the book, I urge readers to ride the M29 bus. The city's extraordinary transportation system promotes certain bus lines (100 and 200) because they access some of the famous sites, like the Brandenburg Gate and Unter den Linden. The M29, on the other hand, offers a chance to see every kind of "real" Berlin — not just Jewish Berlin but the full range of this extraordinary place, from the raffish world of Neukölln in the East through multicultural Kreuzberg, past the Jewish Museum and the great department store KaDeWe, whose sixth floor is one of the world's great gourmet paradises, on to the international shopping heaven of the Ku’Damm and from there to the glorious mansions of Grunewald, where upper-crust Jewish families like that of Walter Benjamin resided. It takes an hour from one end of the city to the other, and you've seen a multiplicity of worlds.

The author contemplates the memorial at Track 17, where markers state the dates and numbers of Jews transported by railcars from Berlin to concentration camps in the East. (Photo by Nick Barberio, Office of Communications)

How does Berlin come to terms with its past and inform its cosmopolitan present?

More than perhaps anywhere in Europe, Berlin has taken on the sacred duty of remembrance regarding the traumas of the past. The famous sites are Daniel Libeskind's Jewish Museum and Peter Eisenman's Holocaust Memorial, but in the epilogue to my book I introduce readers as well to a number of quieter, less visited, and therefore in some ways more evocative enterprises of recollection. My text also invites reflection on the purposes of memory, expressing the hope (as the whole book aims to do) that we are recollecting not just the death of a civilization, but also its life.

How has "getting lost" in Berlin reinforced your love of that city?

Here is one instance. My partner and I spend a lot of time in a certain corner of Kreuzberg. Our building is a modest construction from ca. 1900, with graffiti throughout the hallway, and the outside no better. Ditto for other buildings on the block. No tourist comes within several U-Bahn stops of us. Yet one day recently, we walked around the corner in a direction we hadn't traversed, and there we encountered a little 19th-century bridge over the Kreuzberg canal. As we gazed westward along the water, what lay before us was a landscape of weeping willows as far as the eye could see; we felt we had traveled from Gritty City to the English Lake District.