Nolan McCarty is the Susan Dod Brown Professor of Politics and Public Affairs. His research interests include U.S. politics, democratic political institutions and political game theory. He joined the Princeton faculty in 2001.

Nolan McCarty, the Susan Dod Brown Professor of Politics and Public Affairs, reflects on his experience as a first-generation college student, the ways he connects with first-gen students at Princeton, and his passion for running.

McCarty has co-authored three books: "Political Game Theory," "Polarized America: The Dance of Ideology and Unequal Riches" and "Political Bubbles: Financial Crises and the Failure of American Democracy." He earned his bachelor's degree from the University of Chicago and his Ph.D. from Carnegie Mellon University.

In the Q&A below, he reflects on his experience as a first-generation college student, the ways he connects with first-gen students at Princeton, and his passion for running.

How would you describe your childhood?

I grew up in Odessa, Texas, a working-class oil-field town. It's mostly known as the setting for the book and movie "Friday Night Lights," whose events take place while I was in high school. It’s worth noting however, that the book was about the “rich” high school in Odessa — I went to the other, more downscale one.

Odessa was great in a lot of ways, but preparing kids for elite colleges was not one of its strengths. Not only had my parents not completed college, but I did not know any adults (other than teachers) who had.

What is your strongest memory of being a first-gen college student?

When I entered the University of Chicago I felt really out of place. I had no idea how universities worked or what to expect in my classes. When I struggled a bit in the first quarter, it was tough not to have anyone from Odessa whom I could ask for advice. There was also some significant culture shock, moving from a small town in the Southwest to a big Northern urban city.

While it may seem like a mundane thing, one of biggest challenges was buying a proper coat for a Chicago winter. I asked a classmate from Chicago where to buy one, and she sent me to Marshall Fields. Upon arriving, I found out that the cheapest coat in the whole store was more than my spending money for the entire semester. So I left empty-handed. It was a very cold two months before I swallowed my pride enough to ask where “someone like me” should go to buy a coat.

How are you involved with first-gen students at Princeton?

Until four or five years ago, there wasn’t really any way for me to identify first-generation students or for them to identify me. Then the University set up a series of dinners to get first-gen faculty and students together. These are terrific events, and I attend whenever I can. I really enjoy hearing the students’ stories and sharing mine.

I come away from each dinner with a deeper appreciation of the challenges of maintaining economic diversity at a place like Princeton. As our country faces widening inequality and declining social mobility, efforts to recruit and retain low-income and first-generation students are more important than ever.

McCarty and his colleague Nick Feamster (left), professor of computer science, are regular running buddies — hitting the track, paths and trails on campus and taking longer runs through the outskirts of Princeton.

What advice do you have for first-year, first-gen students?

I think the moral of my coat story is that first-generation and low-income students should never be afraid to ask questions or to ask for help. That everyone else seems to completely understand how Princeton and higher education works should not be a source of any embarrassment or anxiety. The faculty and administration really want first-gen/low income students to succeed.

You can also be spotted running on campus. How did you get started running?

I started running relatively late in life. When I was in high school, I thought about applying to the Air Force Academy. Their application required that I report my time for the mile. When I realized I couldn’t actually run a mile, that was the end of my career as a fighter pilot. I didn’t try again until I was an assistant professor and wanted to lose some of the weight I had gained as a graduate student. After a few months, I was hooked. Now I run every day and somewhere between 50-60 miles a week. I do about 20 races a year and have finished 10 marathons. I also compete as part of a master’s distance running team for the Shore Athletic Club.

Runners often talk about a ‘zone.’ Do you experience that?

I don’t know about a zone, per se. But I feel much better physically and psychologically on the days that I run. Running is a great stress relief. Some people say running gives them time to think. For me, running gives me time to not think.

Do you have a running buddy?

I often run with Nick Feamster, a computer science professor, who is the much better runner. We discovered each other on a social media site for runners and cyclists called Strava and then bumped into each other at an academic cocktail party. We usually run together twice a week when we are training for marathons. We do a track workout on Tuesdays and a long run on Sundays. Our long runs usually take us to Hopewell or Montgomery and back. Lots of hills. We mostly talk about running and injuries, but occasionally Donald Trump.

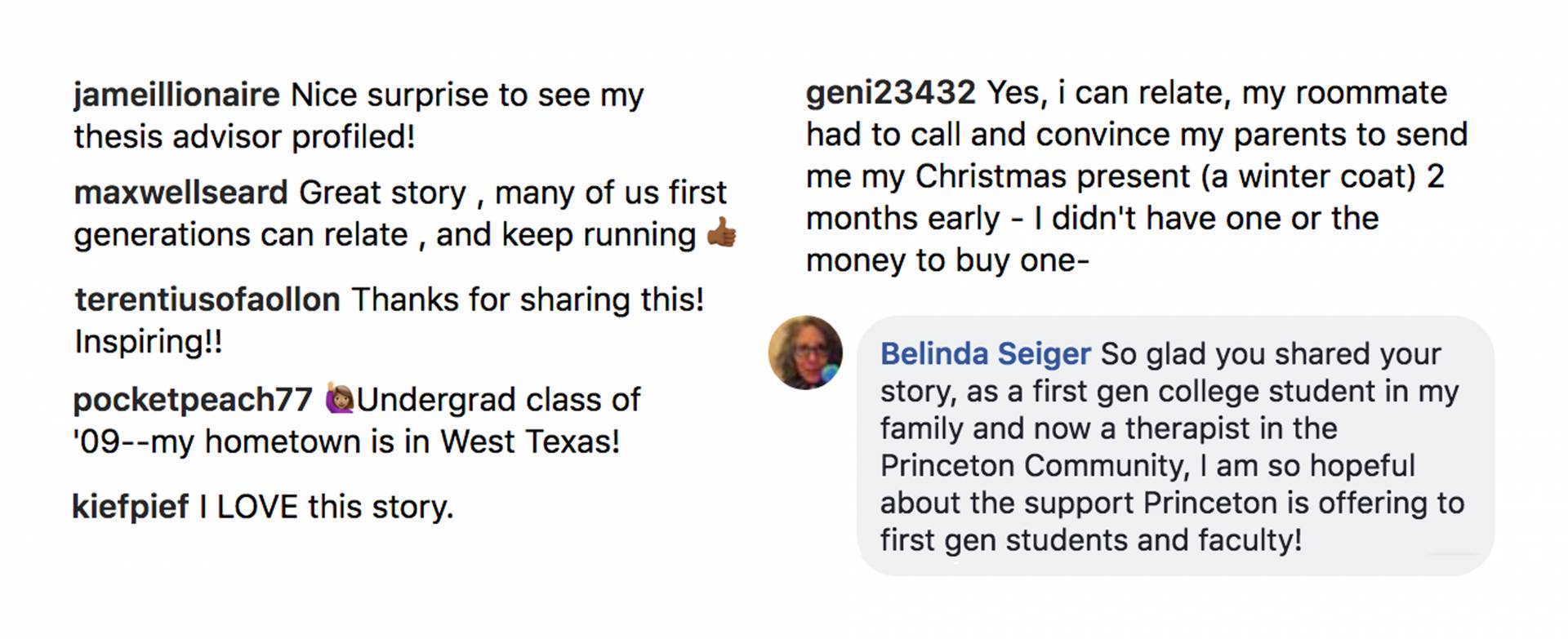

Social media reacts

A condensed version of this story appeared on Princeton's #TellUsTigers Instagram series and Facebook page, garnering hundreds of "likes" and comments, some of which appear below.