Since he was a child, Princeton University senior Dayton Martindale has loved science. So much so that after he receives his bachelor's degree in astrophysical sciences this year, he doesn't want to be a scientist.

He wants to be the person scientists need to help bring their research before the public. Martindale wants to help the average person understand the importance and influence of the work that occurs in the laboratories they'll never see, and that comes out of the fields they'll never study. He wants to be a science writer.

"What got me into science in the first place were Stephen Hawking books, and Neil deGrasse Tyson on television, and museum exhibits," said Martindale, who will begin the master's program in science and environmental journalism at the University of California-Berkeley in the fall. "I realized that if presenting science to the public is what I'm more excited about, why not do that?"

In an unusual (but not unheard of) turn, Martindale's senior thesis has not had him studying data from a large survey project, or detecting cosmic motion betrayed by infinitesimal fluctuations of light. He has instead drawn upon recent research from the Hubble Space Telescope to construct a narrative that explores the trajectory, timetable and consequences of the eventual collision of Earth's home galaxy, the Milky Way, and its closest galactic neighbor, Andromeda.

To help him present complex research in an engaging and accessible narrative, Martindale worked with two advisers: Neta Bahcall (right), the Eugene Higgins Professor of Astronomy, who has presented numerous public talks about science, and noted science writer Michael Lemonick (left), a writer-at-large for the nonprofit Climate Central and a Princeton visiting lecturer in astrophysical sciences, freshman seminars and the Princeton Environmental Institute. (Photo by Denise Applewhite, Office of Communications)

Martindale chose his senior thesis topic after three years in one of Princeton's most rigorous undergraduate programs. Aspiring astrophysicists must, in addition to the senior thesis, undertake two semester-long junior research projects, many of which go on to become published papers. One of Martindale's junior papers and an optional summer paper after his sophomore year took the form of traditional research. "I definitely found those experiences valuable, but I realized that I didn't want to be a pure researcher," he said.

He restructured his junior paper into a narrative story about Princeton's Gáspár Bakos, an associate professor of astrophysical sciences who focuses much of his research on exoplanets and oversees planet-hunting networks that have discovered more than 50 planets since 1999. Martindale's story appeared in the winter 2015 edition of the magazine Mercury.

The experience prompted him to approach his thesis adviser Neta Bahcall, the Eugene Higgins Professor of Astronomy, with the idea of writing an in-depth article rather than a research paper for his thesis. Bahcall, who has directed the department's undergraduate program for 20 years, said that while Martindale's approach is uncommon, other students have wanted to apply their formal science education to writing, education or public policy.

"I tell students that this department is very flexible and will support them in any direction they want to go in that is connected to science and astrophysics," Bahcall said. "It is important for us to produce outstanding scientists and we do that — some of them are top scientists around the world. But it's also very important to produce science policymakers, educators and writers who will be leading science advocates in the community."

Martindale "found his call in combining astrophysics and science in general with journalism," Bahcall continued. "He writes beautifully and he's very interested and passionate about writing good articles of high scientific quality to educate the public. If we can get a wonderful science writer to write in publications or science books, it's a wonderful thing to have."

For additional guidance on his senior thesis, Martindale reached out to noted science writer Michael Lemonick, a writer-at-large for the nonprofit Climate Central and a Princeton visiting lecturer in astrophysical sciences, freshman seminars and the Princeton Environmental Institute. Lemonick had previously co-advised Martindale on his junior paper.

After Lemonick came on as Martindale's second adviser, he, Martindale and Bahcall, who has presented numerous public talks about science, worked to find a topic that would be publicly compelling and novel. They initially considered an article about the invisible and theoretical forces of dark matter and dark energy — Bahcall's specialty — before their discussions came to a topic that piqued Martindale's interest: the eventual collision of the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies.

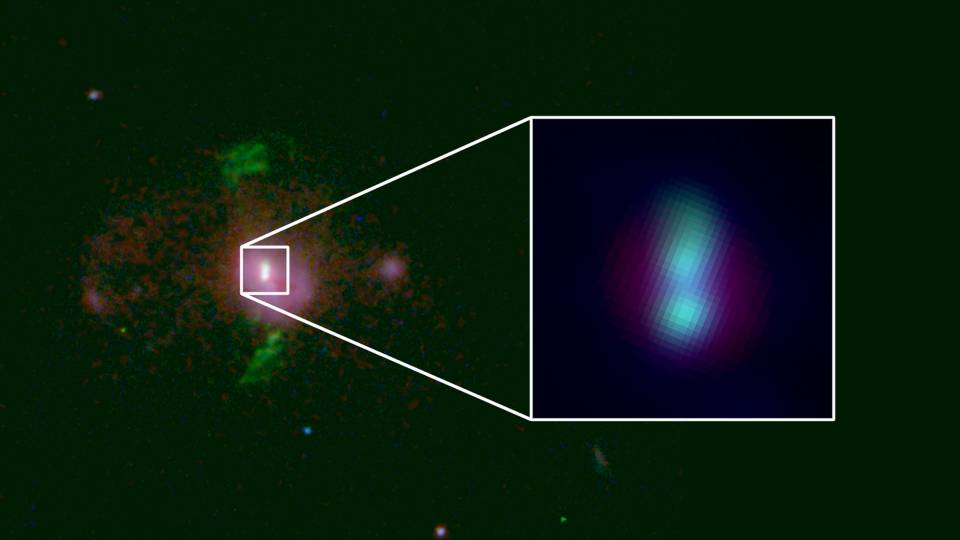

This NASA illustration shows the collision paths of the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies as gravity pulls them toward each other. In the rear is the smaller galaxy, Triangulum, which may be part of the collision. At right, the sun marks the position of the Earth's solar system, which, given the amount of empty space in both galaxies, should survive the merger as long as the sun remains intact. (NASA; ESA; A. Feild and R. van der Marel, STScI)

Galactic collisions are somewhat of an anomaly in a universe that's expanding behind the outward push of dark energy, Bahcall said. Galaxies such as Andromeda and the Milky Way, however, are close enough that their mutual gravitational pulls will continue to draw them toward each other in what Bahcall called a "circular dance" until — about 4 billion years from now — they eventually merge. (Though given the amount of empty space in each galaxy, Earth will likely emerge unscathed as long as the sun and solar system remain intact, Bahcall said.)

Central to Martindale's thesis were 2012 research papers based on Hubble data that determined the lateral speed of Andromeda's motion toward the Milky Way — roughly 17 kilometers per second (which is not very fast for an object that's 220,000 light years in diameter). This information had long been missing from studies on the collision. Andromeda is not coming at the Milky Way head-on — it's moving in diagonally, meaning that it's coming forward and from the side (laterally). Since the early 1900s, astronomers only had data on how fast Andromeda was moving forward, but not how fast it was moving laterally.

Martindale has proven himself as an astrophysicist and a writer on a project that required him to make a complicated topic accessible and interesting to a lay audience, Lemonick said.

"Some people with a science background have real trouble getting themselves out of the weeds — which is what a science writer needs to do — and thinking the way a non-scientist needs to think," Lemonick said. "But some scientists are good at it and Dayton happens to be one of those scientists. He doesn't need to be led by the hand to make something accessible because he has that instinct to know what he needs to do."

Writing has been a feature of Martindale's life, both while growing up in Oak Park, California, and during his time at Princeton. An enthusiast of social and political issues, he has co-written op-eds for the student newspaper, The Daily Princetonian, and writes about culture and campus issues for the student-run Nassau Weekly.

A general interest in social issues prompted Martindale to spend the past two years as a tutor at area youth correctional facilities for the Petey Greene Program, an inmate-education initiative that began at Princeton before being founded as an independent nonprofit in 2009. He got involved because he initially thought of becoming a teacher.

"I no longer want to be a teacher, but getting to know the incarcerated has been a powerful and educational experience for me, especially as someone who grew up in a quiet suburb," Martindale said. "I have since read a lot, attended events and even done some activism regarding mass incarceration. It's definitely something I'd like to write about if my journalism career pans out."

Martindale, who wrote fiction as a child, has as an adult embraced what he sees as the informative power of nonfiction, especially if it seeks to advocate. Martindale believes that advocacy is often lacking from news and nonfiction writing, particularly in regard to science and climate change.

"It occurs to me there is a science-literacy gap. There are a lot of great nonfiction writers, yet I feel the news doesn't do a great job of reporting social issues, particularly related to science," Martindale said. "I don't think it would be a bad thing to have climate-change writers with a political bent who also are scientifically literate."

Martindale is particularly passionate about relaying the scientific, social and political issues behind climate change to the public, and hopes to make that his career. He feels that the scientific consensus on climate change has caused journalists to drop the mantle of advocacy.

"I feel like many writers are happy to know there's a scientific consensus on climate change because now they can let the issue drop as if it's been decided," Martindale said. "But consensus is not an excuse to stop talking about it."

These NASA photo illustrations depict the various stages of the merger of the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies, as it would appear from Earth. The first-row images depict the present arrangement of the galaxies (left) and the galaxies 2 billion years from now as Andromeda draws nearer (right). On the second row, the sky is dominated by Andromeda 3.75 billion years in the future (left) with new star formations appearing 3.85 billion years from now (right). In the third row, star formations continue 3.9 billion years from the present (left) with Andromeda becoming stretched and warped by the Milky Way's gravity as the galaxies collide at the 4-billion-year mark (right). In the fourth row, the galaxies' cores appear 5.1 billion years from now (left) and finally, after 7 billion years from the present day, merge into a single, giant elliptical galaxy. (NASA; ESA; Z. Levay and R. van der Marel, STScI; T. Hallas, and A. Mellinger)

Lemonick found Martindale's ardor for journalism just as encouraging as his abilities, he said. "Most students I have are interested in journalism in that they want to try their hand at it, but they don't really intend to go on and pursue it as a career," Lemonick said. "Just the fact that he's interested in this as a possible profession makes him different. And he wants to get better — that's the other hallmark of someone who is serious."

Martindale's project presented numerous challenges as an aspiring journalist, he said. Foremost was that he wasn't writing about people.

"My main characters are the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy, which are intriguing in their own ways," Martindale said. "But I'm used to writing about human subjects who are easy to craft a narrative out of. So to do that with these galaxies is a very different but interesting experience. I'm not following any one person's arc — I'm following the galaxies' arc."

Martindale's senior thesis also has been a philosophical experience for him, he said. The Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies move and interact on timescales of billions of years. Other writers on the topic have employed the pronoun "we" to refer to the Milky Way as if humans will be around to see the galaxies merge, Martindale said. He has instead realized that humans play no role in the massive dealings of the universe, and won't — and haven't — been around to witness most of it.

"Stories that happen at these scales keep me humble about humanity's place in the galaxy," he said. "Even if we survive climate change and continue for thousands of years, we're talking about billions of years here. Who knows what the state of intelligent life will be, or the state of life in general?"